When the World Health Organization classified COVID-19 as a global pandemic, it seemed much scarier to me than any of the more recent viral threats like SARS or H1N1. There are a lot of reasons why this all feels different and much bigger; seeing our local grocery stores as crowded and empty as those on TV is probably one of the most unsettling. This got me wondering about the 1918 Influenza Pandemic and how San Pedro fared through it all. What I found could be partially described as “similar situation, different century,” and the rest is a sobering look at the potential for loss of life here if things get really bad.

On September 25, 1918, the San Pedro Daily Pilot printed this small blurb on page 2, “Spanish influenza is just the same old ‘flu’ that for years, at irregular intervals has caused Americans to sneeze their heads off.” A week later, all schools, churches, and theaters would be shut down as part of a citywide limited quarantine. There weren’t any stories about a run on local markets because the nation was in the midst of World War I and already under strict rationing orders.

The war effort was partially responsible for the quick response in restricting local groups from convening because keeping the flu out of the shipyards was a major priority. All visitors were banned from visiting shipyards, and all public ship launches were canceled. Fort MacArthur and the Navy Training Center were both under strict quarantine, while the submarine base was still open.

Right away, health officials knew that the small San Pedro Hospital in the old Clarence Hotel wouldn’t be enough to care for all of the sick. A group of local civic leaders held an emergency meeting to figure out a solution. The first idea was to erect a tent hospital on the Dodson Ranch (Vista Del Oro). Rudecinda Sepulveda de Dodson had granted the use of her property, but a severe nurse shortage kept them from going that route. The L.A. Board of Education refused the use of San Pedro High School, so a temporary isolation hospital with 25 beds was opened at the San Pedro Women’s Clubhouse at 11th and Gaffey Streets. The hospital was supplied and staffed by the local chapter of the Red Cross that had been organized the previous year. The first course of action was to ask that every available nurse, graduate nurse, person with first aid knowledge, and those who felt confident enough to care for others apply to the Red Cross to help in the effort. Getting answers proved difficult because some feared taking the illness home or worried about getting paid for what was sure to be hard work.

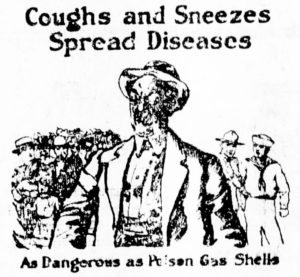

A newspaper ad during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (photo: courtesy San Pedro Heritage Museum)

After a month of limited quarantine, the effects of the pandemic were evident all over town. Businesses that were allowed to stay open were operating with limited staff, an isolation hospital for the submarine base was opened on top of Warehouse One, and limited supplies were forcing people to get creative by using coffee filters for masks. The flu had four out of five fishing boats laid up with sick crews. Eventually, some fishermen were too afraid to go fishing in case they got sick far from shore. This led to a shortage of everyday types of fish that locals relied on for Friday meals. Flu deaths began to rise within a couple of weeks of quarantine, and it didn’t discriminate. Babies, children, young people, the old, and even the military under strict quarantine were all among the victims of the virus. The saddest stories were the multiple deaths in a single household, happening in such quick succession that a double funeral was possible. Generally, funerals weren’t allowed to take place inside of mortuaries or any building; services were only allowed at gravesite.

Eventually, the number of deaths and new cases began to subside. By late November, things started to improve; fewer people were sick, and the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday made them restless to get back to some semblance of a normal life. The local theater operators who had taken the biggest financial hit were also eager to get back to business as usual. The Victoria Theatre had initially made light of the situation, putting “Now Playing – Spanish Flu” on their marquee, but by November 21, theater operators, in true San Pedro fashion, passed around a petition to get the health authorities to lift the quarantine. Some even started booking events in hopes that the public support would pressure officials to lift the ban. F.O. Adler of The Victoria even tried to get an injunction, but their efforts were all in vain. The health authorities replied to the restlessness in San Pedro by hiring soldiers and sailors returning from war to help enforce social distancing requirements, some even getting arrested for not following the law.

This extra enforcement was short-lived, and the quarantine was lifted in early December. Theaters opened December 2, kids went back to school December 3, and the isolation hospital closed December 6 due to a lack of patients. For all intents and purposes, the epidemic was over. Schools closed again December 11 because cases started to spike again, and home quarantines were enforced, but a citywide quarantine was not ordered again. spt

Comments