“People like to create their own image of Yuri, one that matches their own politics and comfort zone.” – Diane C. Fujino, author of Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama.

This month, we celebrate the centennial of a woman who is remembered in very different ways depending on where you’re standing — in San Pedro, her beloved hometown, or Harlem, her “university without walls.” For this occasion, let’s transcend political comfort and blend the images of San Pedro’s Mary and Harlem’s Yuri to give you a fuller picture of who Yuri Kochiyama was.

Yuri Kochiyama was born Mary Yuriko Nakahara in San Pedro on May 19, 1921, a birthday she shares with Malcolm X, the radical civil rights activist who would shape her political ideology in adulthood. At her core, Yuri Kochiyama loved people and believed in justice. She had a sharp mind with a savant-like memory for names and details, her heart was big enough to hold humanity at its center, and her hands were always busy in service to her ideals. An infectious enthusiasm radiated from her, and everyone caught in its path willfully surrendered to its demands. She was popular, inclusive, and hospitable to a fault. For all of this, Yuri Kochiyama was a radical.

Yuri’s politics made her a revolutionary. She was one of the only Asians in the radical Black movement in Harlem during the 1960s and ‘70s. She was a Black nationalist who believed in self-determination (liberation through Black nationhood) and self-defense (which included gun training). After World War II, Yuri moved to Harlem with her husband Bill Kochiyama to start a family. Racism against Japanese Americans still limited employment opportunities, so the Kochiyamas relied on public housing afforded to veterans. Yuri called Harlem her “university without walls” because living there provided her an invaluable education on racism, especially the oppression and discrimination faced by African Americans. As Harlem grew into the epicenter of the radical Black movement, Yuri began to change right alongside it. Her involvement started with civil rights marches and protests. Eventually, she put her writing and natural networking skills to use until she became an integral part of the movement.

Of all the radical movement leaders that Yuri met and worked with, Malcolm X had the most significant impact on her. She admired his service, courage, search for truth, and the direction he provided for his people. It was Malcolm’s ideology that Yuri would use as a standard to measure against all others and ultimately convince her to support Black nationalism. In 1969, at the age of 48, Yuri joined the Republic of New Africa and adopted her Japanese middle name instead of her American first name, Mary. As a revolutionary nationalist, Yuri opposed imperialism. She believed that freedom fighters were justified in defending their country from imperialism by any means necessary. This led to her defense of controversial political prisoners, including Puerto Rican nationalists who had assaulted Congress in 1954, wounding four. In 1977, Yuri took part in occupying the Statue of Liberty to protest their imprisonment and pressure the government to release them.

As one of the tens of thousands of Japanese Americans incarcerated by the U.S. Government during World War II, Yuri became one of the leading voices in the Japanese American Redress movement. Her work within the revolutionary Black movement prepared her to take a principal role, becoming both a mentor and a passionate speaker. She became someone younger activists in the greater Asian American movement could look to for inspiration and guidance. President George H.W. Bush signed an official apology to the incarcerated Japanese Americans in 1990, and all living internees were paid $20,000 in reparations for the government’s violation of their civil rights.

Although she had been part of protests and marches, was under surveillance by the FBI for her connection to radical Black activism, had occupied the Statue of Liberty, and had been part of a successful redress movement, the name Yuri Kochiyama only appeared in the San Pedro News-Pilot once, in her older brother Art’s obituary. As far as San Pedro was concerned, she was still their beloved Mary.

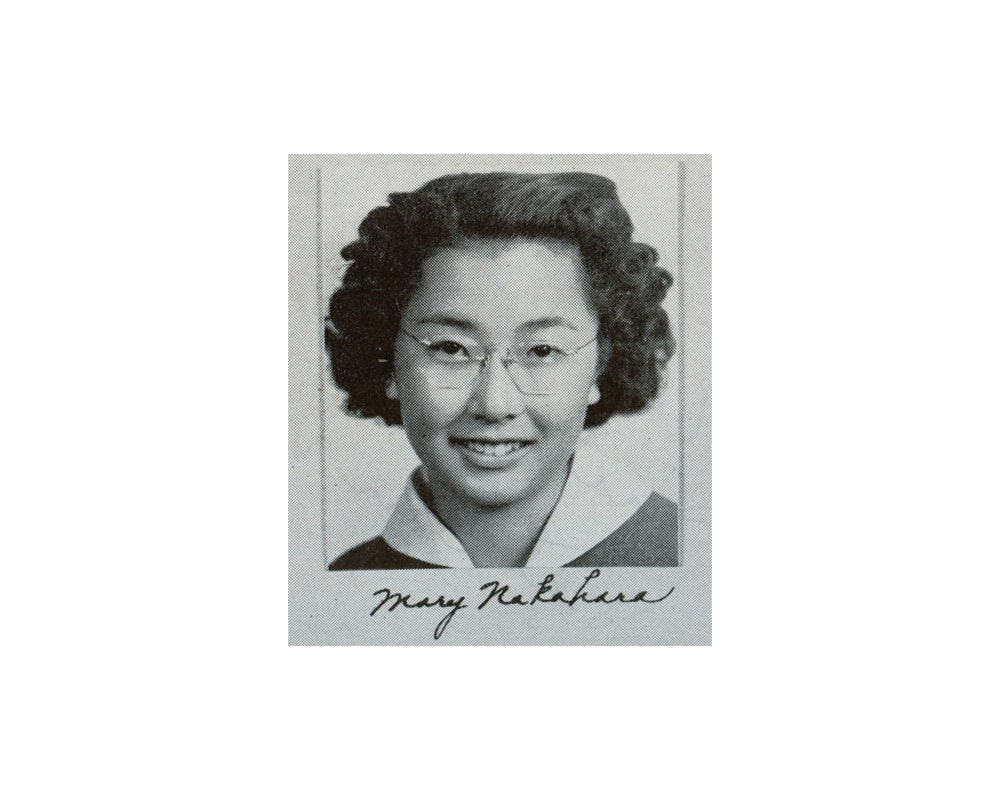

Mary Nakahara had a very typical Pedro pedigree. She attended Fifteenth Street School, Dana Junior High, and San Pedro High with her twin brother Peter. Although they were Japanese, the Nakahara family lived at 11th and Meyler streets, outside of the typical redlined area that most minorities were relegated to in San Pedro. Mary was an extremely popular student at the high school, so much so that she became a legend in her own time. Not only was Mary the first girl in school history to be elected student body vice president, but she was also the first girl to ever receive a boys’ varsity letter. The latter was due to her fanatical dedication to high school sports.

Mary was an unabashed sports nut. Los Angeles didn’t have any professional sports teams, so she devoted herself to the high school teams. Mary was an assistant editor for the school paper, the Fore ‘N’ Aft, but did most of her sports reporting for the News-Pilot. When she felt like the tennis team wasn’t getting enough coverage, she wrote to the sports editor and offered to write a column for free. No matter the distance, armed with a camera and notepad, Mary rode her bike to all of the tennis matches. One famous story included the tennis team spotting Mary riding her bike out to their match in Santa Monica and picking her up (this was before freeways).

Besides publicity, Mary offered the athletes an unlimited supply of support and school spirit. Her infectious enthusiasm made people pay attention and earned her the admiration of the athletes and coaches and a seat on the bench at every game. Mary would carry her love for San Pedro athletics with her wherever she went. She reported on softball games inside the Santa Anita processing center during the war. She kept tabs on local teams from Harlem. Every time she saw Willie Naulls play for the Knicks, she made sure everyone in Madison Square Garden knew he was from San Pedro.

This font of unlimited spirit was the girl that San Pedro adored. She was celebrated nearly every time she came home. Once, an impromptu reunion happened when 200 people bought tickets to lunch with her on the Princess Louise. In Mary’s case, you could go home again; you just had to leave your controversial politics at the door. For several years, Mary produced a holiday newsletter that told about her life in New York. As she began to get more political, the content was uncomfortable for many of her friends in San Pedro, so she ended it.

There isn’t much difference between San Pedro’s Mary and Harlem’s Yuri. Whatever you called her and however you saw her, she was always motivated by love and what she felt was the right thing to do. The stakes were just higher outside of San Pedro.

To learn more about the life and politics of Yuri Kochiyama, please join us on May 19 at 7 p.m. for a Heritage at Home presentation. To attend, please email angela@sanpedroheritage.org. spt

Comments